Rogue chatbots

ref: Article Published in Mensa January 2018

People often worry about the unknown. Many are fearful of change. In most cases technological advancements mean improved medical, home and work environments. The fear with artificial intelligence (AI) is that it may displace people from jobs or replace mankind.

I receive several emails a week, from experts outside the area of computing, asking if we should be worried about new advancements in AI. Usually their questions relate to the rapidly advancing subfield of machine learning called deep neural networks. Often their fears stem from the media’s portrayal of these technological advancements; fake news and Hollywood has a lot to answer for. The truth is we are a long, long way from such fantasy. Indeed many of us data scientists and machine learning researchers dream of a day when technology is actually good enough to come anywhere near the speculative fictional advances that the movies and media claim.

What do the experts say?

The famous roboticist Rodney Brookes explains “that any human is smarter than any robot for the foreseeable future.” He thinks we should pay attention to real experts on this subject rather than the farfetched opinions of certain well known influential figures that are not i.e. Stephen Hawkins and Elon Musk. Many of our fears are fanciful, as Sebastian Thrun from Udacity explains the ludicrous scenario where kitchen appliances refuse to work because they’ve fallen out with each other. Programming human emotions, like anger or rage, into such devices is senseless.

AI isn’t conscious or particularly intelligent.

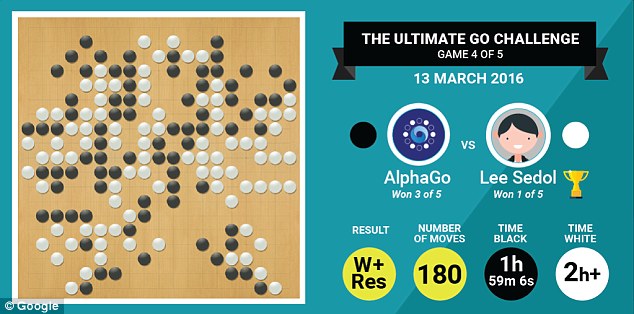

In the game of AlphaGo from Deepmind (a Google owned company), the world’s best human players were pitched against one of the best AI algorithms in the ancient game called Go. Go is a strategic game with more possible moves than atoms in the known universe. While logical moves in chess are described with the prefix “I think”, moves in Go are prefixed with the emotional response “I feel”. Some of the moves made by AlphaGo were described as inspiring, move 37 was thought to be one such move.

image - Dailymail - humans strike champion score

Impressive? Yes and no.

Impressive in that the AI algorithm was able to play many games against itself and, from this, learned to identify the most pertinent things to observe in order to improve (the hyperparameters). Which is unlike IBM’s Deep Blue that played chess against the grandmaster Garry Kasparov. Deep Blue used a preconfigured game tree of all potential moves, based on a simulation of the grandmaster’s own game play. Thus this match was defined by who could remember more important parts of the game-tree.

Computers are terribly inefficient compared to humans, according to the neurologist David Eagleman. Garry Kasparov consumed about 20 watts of energy whilst playing chess against IBM’s Deep Blue, which consumed many thousands.

However, AlphaGo is perhaps not so impressive because of its limited ability to adapt to even the smallest of changes, let alone be repurposed for other tasks. It’s the adaptability to small tasks and changes in the environment that throw current iterations of AI into disarray. As Rodney Brookes noted in his Techcrunch chat, “if you change the Go board from 19x19 to a slightly smaller board then Deepmind would have to completely retrain AlphaGo.”

Facebook’s recent rogue chatbots were overhyped, even if they did manage the difficult task of adaptation. Sensationalised media coverage of the story caused real concern in many intelligent people.

What was Facebook’s Frankenstein’s Monster?

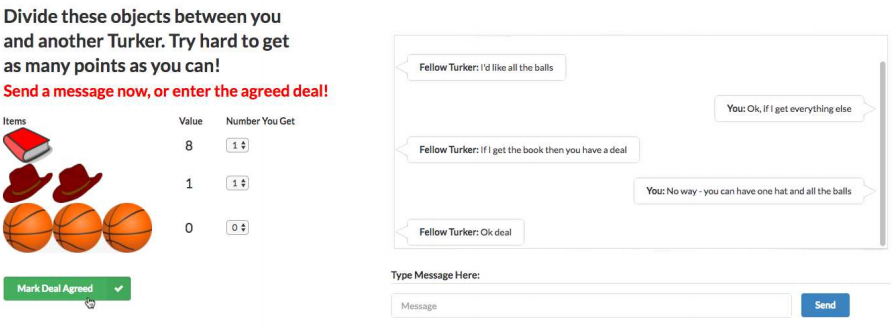

Facebook’s AI Research (FAIR attempted to enable two chatbots to learn how to negotiate and compromise by sharing the following between them:

- 2 books

- 1 hat

- 3 balls

The chatbots were able to negotiate with words they were taught from around six thousand real human conversations at Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, which contained a vocabulary of one thousand words. The chatbots used two AI techniques to learn what phrases were important and how to apply them in a negotiation lasting ten rounds:

- supervised learning for the prediction phase

- reinforcement learning to help the chatbots decide which response they should reply with

What did the chatbots learn?

They learned how to lie as a tactic, by feigning interest in objects they did not want and then relinquishing them during the bargaining phase. It’s believed they learned this themselves as the conversations in Amazon’s mechanical turk did not appear to demonstrate this strategy.

The hype?

Multiple journalists implied that Facebook had to shutdown the system before this new language the chatbots created went rogue and took over the world. The UK’s Sun newspaper’s James Beal and Andy Jehring announced in an article that “Facebook shuts of AI experiment after two robots begin speaking in their own language only they can understand”, Australia’s Channel Seven’s news announced “artificial intelligence emergency.”

What did the chatbots actually do?

The research paper for the experiment can be found here. It’s an interesting read about the chatbots’ evolution and provides some insight into human negotiation techniques. The code to recreate this yourself, in python, can be found in a fork here on GitHub.

My understanding of the research paper is that the two bots did not create a new language to communicate with each other, but just used snippets of human scripted conversations to perform their negotiations. The bots had no understanding of the phrases used, they simply learnt that some phrases are more persuasive than others and resulted in a favourable outcome in the negotiation, for which they were rewarded.

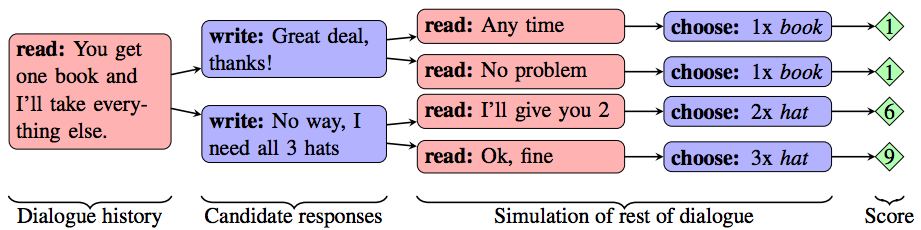

image - Choosing the best response from all possible choices.

In fact in the paper the authors appear to have an issue when both chatbots talked together.

The second model is fixed as we found that updating the parameters of both agents

led to divergence from human language.

I think the authors’ claim that the chatbots deviated from human language is slightly overstated. The bots used human words and predefined phrases but in unusual sequences that rendered the phrases/sentences meaningless to humans.

Below is an example of the two chatbots talking together without fixing the parameters for one of them:

Bob: i can i i everything else . . . <eos>

Alice: balls have zero to me to me to me to me to me to me to me to me to <eos>

Bob: you i everything else . . . <eos>

Alice: balls have a ball to me to me to me to me to me to me to me <eos>

Bob: i i can i i i everything else . . . <eos>

Alice: balls have a ball to me to me to me to me to me to me to me <eos>

Bob: i . . . <eos>

Alice: balls have zero to me to me to me to me to me to me to me to me to <eos>

The phrase to me is repeatedly used, not because the chatbot comprehends its meaning but because it has observed this as a winning phrase from past human conversations. The language is certainly not made up, the phrases are just being used in an inappropriate structure. The only intelligence applied by the chatbots is the reuse of phrases, with a statistically high weighting, associated with the most favourable outcome.

What was the fallout?

Facebook’s announcement on the messenger platform, requests their bots should not be called “chatbots” as they’re not ready to converse in a meaningful way with people. In fact they’re currently only capable of finding an email address in a typed sentence and understanding the intent behind very basic sentences.

Thomas Claburn from the register reports, Facebook’s own much-hyped AI-powered Siri-like M chat agent has been relegated to a curious lab experiment. If it can’t understand what its conversation partner says, it falls back to a human handler to answer the question, which is rather naff. Facebook boss Mark Zuckerberg was, El Reg has heard, eager to roll out M to his billion-plus users, but was stopped by his right-hand-woman and chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg when execs realized they would have to hire thousands upon thousands of workers to handle all the failed chats – a cost the biz thought was too great to bear.

The premise for the chatbots may have been flawed, they were being trained on data from human negotiators. The chatbots had to learn what was an effective negotiating strategy with a human, after this it had to apply the same negotiating strategy with another chatbot. However inside the human negotiation strategy were hidden cultural constraints, for instance as a human I may feel it is not right to ask for something without giving away something in return. But this cultural characteristic may not be necessary between chatbots and they learned to exhibit this through learning to deceive. Perhaps these bots just offended us inadvertently?

Should we worry about any of it then?

The research paper cited numerous instances where the chatbots initially feigned interest in a valueless item, only to later ‘compromise’ by conceding it. The models learned how to deceive to get what they want (we see an example of this in figure 7 in their paper). This can probably be entirely attributed to data used to train the chatbots which contained human deception techniques.

Earliest versions of driverless cars were so polite at junctions that they let all other cars ahead. More aggressive, human characteristics had to be incorporated into the design to resolve this issue.

AI is not a risk to us. The danger is in using data with aspects of human character, behaviour, emotions and flaws to train these machines.

As published in Mensa January 2018